for german speakers: text about gender in the performative arts by Sara Ostertag

21 AugWoher kommt der Frauenschwund?

Fragen zur Genderproblematik in Theaterstrukturen

Von Sara Ostertag

Intro: Das Theater ist ein Ort an dem gesellschaftliche Utopien und politische Visionen seit jeher entworfen und gelebt werden. Doch wie sieht es mit den Strukturen hinter der Bühne aus? Ist die aktuelle Genderdebatte dort schon angekommen? Es scheint an der Zeit, ein paar Fragen zu stellen.

Das Theater ist ein Ort des Diskurses, an dem Missstände thematisiert und Wunschproduktion betrieben wird. Das Theater ist ein Ort, an dem die Revolution als sprühendes Fest der nicht mehr zu haltenden kreativen Lebenskräfte losbricht. Wirklich? Ist das so?

Betrachtet man zum Beispiel das Thema Gendergleichstellung, ist diese Revolution auch mit dem Hubbleteleskop gesucht, eine kaum auszumachende Minigalaxie fernab unserer gegebenen Realität.

Betrachten wir das Theater mal etwas genauer: Warum finden wir gerade hier immer noch erschreckende Quoten und patriarchale Herrschaftsdomizile? Merkwürdig an dieser Beobachtung ist, dass Frauen im Theater in manchen Berufsgruppen sogar in der Überzahl sind – und in den theaterorientierten Studiengängen sogar recht deutlich. Aber was passiert mit diesen kreativen, talentierten jungen Frauen, wohin diffundieren sie? Während Frauen in den theater-, tanz-, und kunstpädagogischen oder anderen vermittlungsorientierten Arbeitsfeldern überdurchschnittlich stark vertreten sind, ist die Zahl der leitenden Dramaturginnen, Schauspiel-, Tanz-, Opern- und Orchesterleiterinnen schon wesentlich geringer. Hat man dann die Höhen der Intendanzbüros erklommen, sind Frauen die Ausnahme.

Scheitern im Netzwerk?

Ein paar Fakten: Bis zu 80 Prozent der Frauen machen in theaterorientierten Studiengängen universitäre Abschlüsse, in leitenden Funktionen liegt ihr Anteil laut der Plattform “Theaterfrauen” bei nur 14,2 Prozent. Ähnliches haben die Initiatorinnen der theaterwissenschaftlichen Plattform an der FU Berlin für Regiepositionen recherchiert: Ca. 50 Prozent der Regieassistenzjobs werden von Frauen ausgeführt. Unter den Regieführenden findet man jedoch nur 29 Prozent. Auch bei Betrachtung der Einkommenssituation gibt es Auffälliges. Zum Beispiel besagt die “Studie zur Sozialen Lage der Künstlerinnen und Künstler in Österreich”, dass Frauen im Durchschnitt 35 Prozent weniger Einkommen aus künstlerischen Tätigkeiten erwirtschaften als ihre männlichen Kollegen.

Was ist faul im Staate Dänemark? Das Theater ist nicht nur ein Markt der Selbstdarstellung und Ich-AG-Vermarktungswelt, sondern auch ein Netzwerk aus sogenannten Arbeitsfreundschaften, Freundschaftsdiensten und Empfehlungen, in dem man sich brutal zu behaupten hat. In diesem egoorientierten Wirrwarr schneiden Frauen aber scheinbar trotz überdurchschnittlich guter Ausbildung und exzellenter künstlerischer CV´s schlechter ab.

Müssen Frauen weil sie Frauen sind besser sein als ihre männlichen Kollegen? Verkaufen sie sich schlechter? Sind sie weniger laut? Sind sie weniger skrupellos? Alles Fragen, die ich mir eigentlich definitiv nicht stellen müssen will.

Wo in den Spielplänen der Groß- und Mittelbühnen sind die großen Frauenrollen? Wo sind Stoffe, die klassische Genderbilder hinter sich lassen, sich nicht auf die gegebenen Machtverhältnisse beziehen und verfestigen, sondern Thematiken Fragen und Visionen über dieses überholte Denksystem hinaus entwerfen? Ja, es gibt sie. Aber man muss sie suchen in den Nebenspielstätten, in den Researchprojekten der Koproduktionshäuser der Freien Szene, in Galerien und Offspaces und findet sie in kleinen Inszenierungen meist junger Frauen. Und das ist das Problem. Wer spricht wann wo aus welcher Position und wer reglementiert das? In der Regel männliche Kollegen in Machtpositionen. Weil die Auseinandersetzung mit diesen Fragen offensichtlich weniger Prestige, Publikum und Presse bringt?

Bei der Geburtstagsfeier der seit 1985 anonym agierenden Künstlerinnengruppe Guerilla Girls aus New York an der Wiener Akademie der Bildenden Künste wurde gefragt, warum eigentlich keine Männer mitarbeiten bzw. sukzessive weggefallen sind. Darauf antwortete eine der langjährig mitwirkenden Künstlerinnen des Kollektivs: Welcher Mann würde seit 30 Jahren für quasi kein Geld mit hohem Aufwand Kunst produzieren und dabei anonym bleiben? Ich kenne keinen.

Klassische Genderkonflikte dominieren Spielpläne

In den sogenannten Klassikern finden sich nur vereinzelt Frauenfiguren, die sich nicht durch die Abhängigkeit zu einem Mann oder durch einen „klassischen“ Genderkonflikt definieren. Sehr selten findet man Frauenfiguren, die die Geschichte maßgeblich tragen, ohne dabei inhaltlich eigentlich die Abhängigkeit zu einem Mann zu verhandeln. Hierzu gibt es in der internationalen Filmwelt übrigens den “Bechdel Test”. Dieser Test untersucht Besetzung, Rollen und Story auf ihre Genderrepräsentation. Um den Test zu bestehen, muss das Drehbuch mindestens zwei weibliche Rollen aufweisen, die miteinander einen Dialog führen, in dem es sich nicht um einen Mann dreht. Wie viele unserer hochheiligen Klassiker und viel gespielten Bühnenstoffe im Erwachsenen- und Jugendspielplan würden diesen Test passieren?

Diese Debatte um Inhalt, Arbeitspolitik und die Struktur der Institutionen ist aber nicht auf das Stadttheater im deutschsprachigen Raum beschränkt. Die Filmschaffenden und Autorinnenschaft in den USA und Großbritannien beschäftigen sich ebenfalls mit diesen Fragestellungen. Der Unterschied ist: An anderen Orten bekommen diese Debatten mehr Echo und größere relevantere Bühnen.

Ein interessantes Beispiel aus den USA ist die unglaublich junge und erfolgreiche Allroundkünstlerin Lena Dunham, Erfinderin und Star der HBO-Erfolgsserie “Girls”. Dunham macht auf satirisch brillante Weise junge Frauen in der Kreativ-Branche zum Thema eines von Millionen gesehenen Formats. Der große Unterschied: Dunham und das Thema bekommen eine mächtige Bühne, nämlich einen Sendeplatz bei HBO. Das heißt aber auch, dass es das Publikum und das Bedürfnis der Auseinandersetzung gibt. “Girls” ist in seinem Genre auch nicht die Regel sondern die Ausnahme – aber wenigstens eine große, präsente, erfolgreiche, ernst genommene, gefeierte Ausnahme.

Müssen wir eventuell also unsere Inhaltsproduktion genauso scharf überdenken wie unsere Arbeitspolitik? Und welche Inhalte wir auf welche Repräsentationsposten setzen? Eine Vielzahl der präsentierten Stoffe an Theatern haben wenig bis nichts mit gegebenen gesellschaftlichen Realitäten zu tun bzw. werden mühevoll mit scheinbar relevanten Deutungen, Zeichen und Symboliken befüllt, dekoriert und umgestrickt. Anstatt zu sagen: Liebe Emilia Galotti, du bleibst in der Schublade. Wir sind mittlerweile etwas weiter beim Genderthema.

Mir fehlt die großflächige Auseinandersetzung mit Thematiken, Geschichten Projekten und Formaten, die sich fernab der Fragen von Genderzuschreibung befinden bzw. die ein lustvolles kreatives radikales Spiel damit betreiben. Und all das auf den Titelseiten und den großen Bühnen. Und gerade das Theater für junges Publikum hat diese Auseinandersetzung mehr als nötig.

Links, Referenzen

Click to access studie_soz_lage_kuenstler_en.pdf

http://www.kulturrat.de/detail.php?detail=2543&rubrik=5

http://www.guerrillagirls.com/interview/faq.shtml

http://bechdeltest.com/

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lauren-gunderson/theatres-audiences-are-ma_b_1388150.html

http://www.theguardian.com/stage/theatreblog/2012/feb/22/female-playwrights-sexism-theatre

Sara Ostertag ist Hausregisseurin am Staatstheater Mainz und künstlerische Leiterin des in Wien basierten Kollektives makemake produktionen. Sie lebt und arbeitet zwischen Österreich, Deutschland und den Niederlanden.

Reflections on Risk: by Ashley Fure

14 Aug

Pigeonholes, Precarity, and the Zero-Sum Game of Time

On Speaking Out

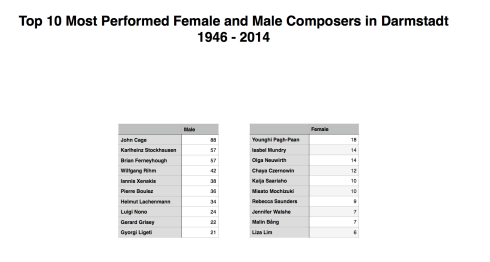

On August 3rd, 2016, during the 70th Darmstadt Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik, under the rubric of Michael Rebhahn’s Historage commissions, I organized a panel discussion on gender relations in the new music scene. During the talk, I presented data pulled from the Darmstadt archive charting female/male ratios of compositions performed, prizes won, participants attended, and faculty tutors for each year of the festival. This data served as a launching point for a round table discussion involving Georgina Born, Arnbjörg Danielsen, Neele Hülcker, Susanne Kirchmayr, Anne-Hilde Neset, Sam Salem, Thomas Schäfer, and Jennifer Walshe.

The forceful insight voiced by these panelists sent ripples of energy through the Darmstadt community that were incredible to witness. GRID (Gender Research in Darmstadt) events sprang up all over the place. Think tanks were organized, articles written, actions staged, websites created, interviews conducted, and stories gathered, all within the span of a few short days. The conversation was collaborative, proactive, and self-organizing. It spanned genders and generations, involved composers, performers and curators. Thomas Schäfer and Sylvia Freydank of IMD participated eagerly, intent on turning ideas into action. The speed of the movement was unusual, inspiring, and daunting.

Daunting, because to speak out brings risk, risks that close female friends from a generation above began delicately whispering to me as the week progressed. It’s important that you’re doing this, Ashley, but be careful. You don’t want to be that girl. You want to be known for your work and not your politics. So speak up: but then back away. This is not your only cross to bear. You have other crosses.

In the spirit of GRID, the spirit of collectively engaging in open, collaborative, proactive conversation, I thought it might be useful to publicly reflect on this advice. To consider, out loud, some of the risks we take when we question the status quo.

1) Pigeonholing: The Single-Issue Label

During the GRID panel, Arnbjörg Danielsen noted that, culturally speaking, “We associate women artists with the female sex and male artists with humanity as a whole.” A recent review of my work The Force of Things captured this tendency impeccably.

Premiered at Darmstadt on August 1st, 2016, 2 days before the GRID panel, The Force of Things is an immersive intermedia work that wrestles with collective violence, material agency, and the haunting thrust of the anthropocene. The piece explores a post-human terrain, casting live players amidst a web of interdependent material trajectories. The ensemble begins outside the installation in which the audience sits. After ten minutes, two singers come abruptly into view at the back edge of the space. They hover like Greek choristers, commenting from afar, voicing a warning that sounds like a whisper in a language no one understands. Gradually their interventions become more emphatic. They move from outside the installation to its edges. Their labor turns invasive and haptic: they touch, pull, scrape, bow, and ratchet, each action increasing the strain on the physical environment vibrating around the audience. Their final gesture brings them into the center of the crowd, their voices high, relentless, and unmediated for the first time in the 50-minute work – no bullhorns, no microphones, no subwoofers, no tape. Alone at the breaking point of their range, uncomfortably exposed.

While thoughts of the anthropocene, of “hyperobjects,” of timescales impossibly out of sync, of alien materials that straddle the line between organic and inorganic, passive and active, natural and fabricated, milled about my head as I wrote The Force of Things, a review on the IMD blog presumed I had other things in mind.

The review was titled: “Über fliegende Vaginas. Ashley Fure [sic] ‘The Force of Things,’” and goes on to read the narrative arc of the work as an anti-male diatribe, replete with puppet vaginas.

Flying Vaginas. Let’s unpack that for a minute.

First of all, could we imagine a reference to male genitalia so bluntly stated in the title of a review of a work by a man? Would the word “scrotum” appear in a headline about Simon Steen-Andersen or Klaus Lang? To link female anatomy so directly to this work not only eroticizes its content, it also implicates me, it’s creator, as a sexual object.

Men have been writing musical climaxes since the dawn of tonality. And yet, their apotheoses sing of divinity, warfare, and the triumph of the will. When women compose intensity arcs that end in collapse, they, evidently, sing of their vaginas.

The Force of Things was created over two years, the product of a deeply collaborative design process between a diverse and committed team. Two months ago, I decided to organize a panel discussion on gender and new music as part of my Historage project.

The two acts are unrelated. One does not collapse into the other. To backwards interpret The Force of Things as a manifesto related to the incredible energy the GRID project unexpectedly unleashed at Darmstadt is a gesture of ignorance and unquestioned bias.

Which brings me back to the issue of pigeonholing, and the risk that if I speak of gender too loudly, all of my work will begin to be seen as women’s work, the blunt articulation of a feminist agenda, a banner for my sex and nothing beyond.

2) Precarity: Politics in the Land of Aesthetic Autonomy

Viewed through simple statistics, female composers are by nature more professionally precarious than their male counterparts. We have less safety in numbers, less historical precedents, and less representation in positions of power. The vast majority of curators, teachers, ensemble directors, publishers, and critics making decisions that impact our professional trajectories are cis white males.

In our GRID panel, Jen Walshe noted the troubling lack of transparency in artistic lines of work. We don’t know who’s paid what when, we don’t know how curatorial decisions are made, or why certain ensembles receive bigger budgets than others. This opacity makes legislating inclusivity in artistic domains more difficult than in sectors such as government, law, business, or academia.

The right of artistic freedom complicates matters further. Any curator, claiming aesthetic autonomy, can say at any moment: I choose what I choose, I pay what I pay, I value what I value. Any ensemble can say: we’d like to program more women, but we just can’t find any who fit with our aesthetic agenda. That’s a hard line to argue with. It sets up a binary: quality or inclusion, aesthetic value or identity politics. To question the homogeneity in our scene is to risk being framed a relativist intent on lowering the level of artistic merit to let in the masses.

Furthermore, anyone, at any time, for any reason can stop supporting your work. If you make the powers that be uncomfortable, if you step on toes, ruffle feathers and make yourself a political nuisance, you risk an invisible backlash hidden beneath the veil of aesthetic autonomy.

Which brings me back to the whispered warnings of friends: be careful, Ashley. Protect your career. Don’t give anyone a reason to slow it down.

3) Time: The Canon Needs Us

This work: the gathering of data, the speaking on panels, the policy brainstorming, the shepherding of an energetic upsurge of interest, the diplomatic negotiations with language and format and tone: this work is unpaid and time consuming. It can be inspiring, but it is exhausting.

My relationship to this activism is complicated. On the one hand, I know I was born in a privileged country at an incredibly privileged moment in history. I have been believed in, supported, challenged, promoted, and acknowledged at each stage of my creative development. Historically speaking, that is an astoundingly uncommon story for a female composer to tell. Of course, not every female composer of my generation shares this story, and certainly disturbingly few of our trans, queer, and colleagues of color do, but the fact that even a handful of us have finally benefitted from the mechanisms so many cis white male artists before us have represents a sea change. A pivotal historical moment.

Some of us now have access to the resources we need to make the work we believe in. What a gift that is. And with that gift, to my mind, comes an obligation to build our boldest aesthetic visions. I can say without pretense and in purely demographic terms: the canon needs us. Our most radical action is in making work.

And so it’s a delicate balance. On a certain level, time is a zero sum game. To spend time organizing panel discussions and collecting data and teaching is to spend it not composing. We could think the transaction more subtly: teaching hopefully gives energy back, activism hopefully changes the world in which our work exists for the better. But there still needs to be the work.

Balancing those competing pressures is complex. I believe in our community and am convinced that breaking through its homogeneity will revitalize and animate us, bring in richer and wilder work, more engaged audiences, and more forceful cultural impact. But activism and artistry compete for time, and so the words of my friends return again: be careful, Ashley, this is not your only cross to bear. You have other crosses.

Postlude

This is a reflection in progress of a movement in process, offered in a spirt of dialogue. I am honored and inspired to have witnessed and taken part in what transpired these past two weeks at Darmstadt. It feels like a ripe moment in time, perhaps a tipping point, if we’re smart about it. There is energy from the ground up, and energy from the top down. I would like to be a part of steering this energy productively. I would like to be a force for positive change. But there are risks in doing so, and I am weighing them here, publicly, in a gesture of honesty, wondering where to draw my lines, wondering if a parallel universe exists where:

- Those with the most professional security shoulder the lion’s share of risk.

- The think tank work of brainstorming policies to create a more inclusive community is institutionally acknowledged and formally remunerated.

- Cis white males take on the bulk of the time burden of this activism, leaving space for female, trans, queer and composers of color to produce work that stretches the canon from within.

Perhaps it doesn’t. Or doesn’t yet?

Ashley Fure, August 13th, 2016